Designed and written by Camille Dubno, edited Witek Wierciski

The Slavs are an ethnolinguistic group belonging to the Indo-European language family, primarily residing in Central and Eastern Europe. They developed as a distinct people more recently than other Indo-European groups, resulting in a higher degree of mutual intelligibility among their languages. However, language—an essential aspect of culture—is not the only factor uniting them. A shared historical memory, particularly of oppression by foreign powers that sought to suppress their identity, culture, and languages, also plays a crucial role.

From the Germanic Prussians and Austrians to the Soviets—who, despite being Slavic, promoted an internationalist identity—many Slavic nations have faced attempts to erode their cultural heritage. Most, if not all, Polish, Ukrainian, Rusyn, Belarusian, Czech, and Slovak grandmothers can recall childhood memories intertwined with the experience of cultural suppression.

However, this has changed since these nations regained their independence. Today, modern Slavic youth are increasingly embracing their cultural identity online in various ways, from fashion and music to even video games.

The modern revival of Slavic identity echoes past efforts to reclaim Slavic classical literature, but on a much larger scale. After the three partitions of Poland, writers such as Adam Mickiewicz and Juliusz Słowacki used literature as a form of resistance against oppressors who sought to erase Polish identity. Similarly, in the 19th century, Czech and Slovak scholars worked to catalog and preserve West Slavic linguistic and literary heritage, fueling national revivals.

This movement, known as Pan-Slavism, persisted across generations as Slavic nations revisited past works and created new ones. Since many Slavic languages were once prohibited under foreign rule, these literary movements became vital for preserving identity and resisting oppression.

While most Slavic nations are now sovereign, a modern, digital revival has emerged. Across the internet, children of Poles, Czechs, Ukrainians, and other Slavs—both at home and abroad—are reconnecting with their heritage through new-age media, blending history with contemporary culture.

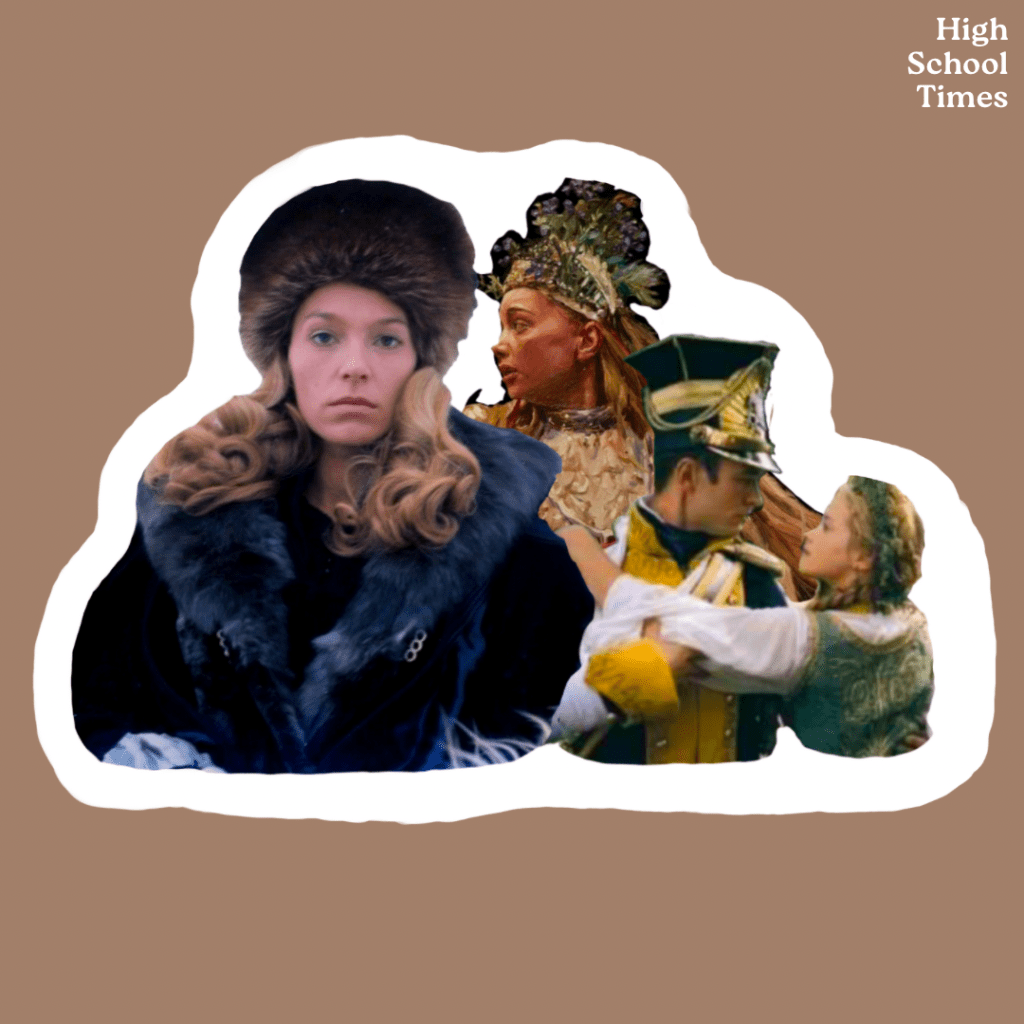

One of the most surprising trends is the rise of the ‘Slavic Doll‘ aesthetic (often referred to as the Slavic or Russian Bimbo, though “Doll” is the more common and accepted term). This figure embodies a hyper-feminine, glamorous take on the classic Slavic woman—adorned in fur coats, red lipstick, beaded accessories, a “babushka” balaclava, and the iconic ushanka hat (which varies in name and style across regions).

This archetypal woman often reclaims negative stereotypes historically attached to Slavic women, such as being materialistic or a gold digger. In many ways, this can be seen as an act of empowerment—embracing materialism in response to the poverty many of these women grew up in. This glamorous sensibility is also reflected in a loosely defined ‘Slavic Doll diet,’ which, according to TikTok users, includes everything from a certain alcoholic drink to bread, kasza gryczana (buckwheat groats), pickled foods, meat, eggs, and even the now-iconic avocado.

Ultimately, while the aesthetic leans into camp, it serves as a playful and expressive way for younger generations to reclaim a cultural identity that was long suppressed. In a world increasingly dominated by homogenized global trends, this resurgence celebrates distinct Slavic heritage—while also paying homage to the many Slavic models who ruled the runways in the 1990s and 2000s.

However, online lifestyle and fashion are not the only ways in which Slavic culture has been reclaimed: music and film have been just as influential. For years now, Slavic folk music and other genres have dominated the cultural consciousness of younger generations. Every week, there seems to be another expertly crafted song by Polish, Ukrainian, or Russian artists, following in the footsteps of hits like GLAMOUR (ГЛАМУР), Moi Marmeladnyi (Мой мармеладный), and V posledniy raz (В последний раз).

This resurgence also extends to larger cultural events such as Eurovision, which for years has brought numerous Ukrainian songs to international acclaim. Similarly, the Polish song Jeśień – Tańcuj, a Eurovision nominee in 2024, gained significant online popularity following the release of the Polish film The Peasants (Chłopi). The movie captivated audiences not only through its musical composition but also with its visually stunning, hand-painted animation. This proud display of Slavic identity reinforces the ongoing movement of the 2020s—reclaiming Slavic heritage and sharing it with the world.

In any discussion of online Slavic representation, the critically acclaimed video game The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt cannot be omitted. Released nearly a decade ago by CD Projekt Red, the game is still considered a landmark achievement in gaming. The Witcher 3 follows Geralt, the titular Witcher, on his journey to find his adopted daughter, Ciri. While I will omit story spoilers—as I believe the game can be enjoyed by anyone—the world in which it is set is distinctly Slavic.

A major factor contributing to this is the game’s source material—a collection of books by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski, who sought to create a fantasy inspired not by Western mythos (such as The Lord of the Rings), but by Slavic heritage and mythology. This influence is evident throughout both the books and the games. However, with the Witcher games being significantly more popular, they introduced Slavic-inspired fantasy to a much wider audience.

Despite the gloomy and often harsh setting of its story, The Witcher 3 captivated players with its Slavic-inspired music, locations, characters, and folklore. This not only speaks to the talent of the game developers but also serves as a testament to the rich cultural heritage of the Slavic people, who for so long were overlooked in global media.

Of course, the glitz and glamour (or rather dull tones of Eastern Europe) of this cultural renaissance have a variety of negative aspects to it. Namely, the Western idea of Eastern Europe, which overlaps with Slavic identity, is often criticized for being too broad or simply an archaic distinction between the “civilized” world and the Slavs. While not inherently problematic—since it does describe the eastern geography of Europe—many nations have begun using different terms, such as “Central European” or “Balkan.” Nonetheless, this is not the central focus of this discussion, as other ethnic groups also inhabit the region. However, it does highlight the historic neglect of these cultures, and the perceived flattening of Slavs in the ‘Slavic Doll’ aesthetic.

Moreover, Slavs, of course, are not a monolith—even this article somewhat perpetuates that misconception. As a Polish person, I have limited knowledge of South Slavic culture, and this article reflects that. Furthermore, the issue of unequal representation within Slavic identity exists not only in Western discourse but also within the Slavic community itself.

While the differences between East Slavic languages are minor enough for their speakers to communicate seamlessly, many Slavs have historically denied smaller groups their cultural sovereignty—that is, recognition as distinct peoples. For example, many irredentist Russians have claimed that Ukrainians, Rusyns, and Belarusians are not separate ethnic groups but merely dialects of Russian, which has fueled numerous conflicts. Similarly, West Slavs are not immune to this issue, as both Czechs and Poles have at times undermined the cultural sovereignty of minority groups within their territories.

Though less prominent, such attitudes persist today. For instance, the Polish Eurovision nominees Niczos and Sw@da performed their song ‘Lusterka’ in Podlasian, a recognized microlanguage. This sparked outrage among certain Polish groups, who dismissed the language as merely a dialect of Polish or Belarusian. While scholars continue to debate the legitimacy of microlanguages, similar disputes extend to much larger so-called dialects or vernaculars (Polish: gwara) such as Silesian, Moravian, or Rusyn—some of which remain virtually unknown.

Finally, the trend also neglects to acknowledge the horrors that Slavic women endured in the “civilized” world during the 1990s and early 2000s, particularly in the modeling industry. After the era of great supermodels in the ’90s, fashion brands began seeking a more “uniform” look—blonde, blue-eyed, and relatively thin. This shift coincided with the fall of the Soviet Union and the opening of borders between the West and Eastern Europe. During this time, young Slavic models became a commodity, exploited in numerous ways while the public admired glamorous runway shows, oblivious to the darker reality behind the scenes.

Moreover, some Western men—often referred to as “passport bros”—sought to exploit the traditional values of Slavic women to justify their misogyny and hatred toward Western women. They claimed that Western women were “too liberal” and lacked the supposed traditional femininity of Slavic women, using this stereotype to promote their own regressive views, and later criticisng Slavic women for being ‘gold digger’s, while they were the ones to initiate the transactionality of the relationship.

This history is often forgotten in today’s “Slavic Doll” trend, reflecting a broader pattern of neglect toward Slavic people and their culture. How ironic—we celebrate the increasing presence of Slavic elements in media and take pride in our cultural independence from past oppressors, yet we ourselves overlook the struggles that Slavic women faced in the 1990s and 2000s.

As someone with a varied Slavic heritage—one that I often fear expressing—I find this trend to be a breath of fresh air when it comes to “internet aesthetics.” However, it must be approached with the nuance it deserves. While the Slavic Doll, with her diet and love for Slavic folk music and film, is endearing, the darker aspects of the trend must also be acknowledged. These include the mistreatment of Slavic models, the oppression of Slavs in etymology, the neglect or denial of certain groups, and the well-known issue of “not all Slavs are the same.” These topics deserve thoughtful discussion rather than being overlooked.

Well, to conclude—Slavic Dolls do eat avocados, whether you like it or not.

Leave a comment